DeepTech Meowsings from K.ATS: Framework for Evaluating Risk in a World of Agents

Access the report to get the insights you need to stay ahead

By: Razvan Veliche, Max Whitmore, Anna Lischke, Junsu Choi, and Rohit Chatterjee

Framework for evaluating risk in a world of agents

In the Generative AI ecosystem rapidly evolving around us, agents started taking a front-and-center position. In this post we will present a point of view and framework for organizing concerns related to agents’ adoption.

Brief overview of agents

Agents are defined as systems which undertake actions on behalf of a user. Specifically, AI agents are based on a Large Language Model (LLM) given knowledge, autonomy and permissions to use other systems (tools) to complete user’s requests expressed in plain language.

Only a few years ago agents were relatively basic, single-purpose tools (simple chatbots and task executors). In a short time span their capabilities evolved and we now have collaborative, multi-agent systems, which can be tuned and even self-learn to follow different objectives (long term decision making, research and exploration, even adversarial b

Just as software is created by enterprises, so agents are designed and implemented by providers which use custom or pre-built components. Agents need three primary components to operate: planning (reasoning and decision-making, usually provided by a large language model or “core LLM”), tools (data or software components, including other agents) and memory (to help track original goal, tasks dispatched and completed, safety and compliant guardrails). The core LLM creates a plan of steps to be taken (executed) to answer the request; the tools may be used in the actual execution of the plan; the memory stores the request, goal, current plan, status of intermediate tasks and their results.

The level of autonomy and tool use permissions distinguish agents from simpler, even AI-driven, apps like e.g. chatbots. Agents can be given detailed information about the tools, or they can discover their capabilities over time, adjusting their planning and execution paths.

Given the power and flexibility of current generation LLMs, it is not surprising to see agents designed around productivity, ecommerce, security, healthcare, human resources and legal support, financial services, entertainment and even personal support areas. From surveying and summarizing thousands of documents, to monitoring and making purchase decisions, to evaluating resumes, to managing calendars, planning vacations and even romantic role-playing, agents are rapidly developed and offered. Agentic frameworks are being developed to help agents interact with and support each other, essentially to create even more complex agents.

Human users’ preferences (time and financial resources, interest, derived utility, privacy concerns) and perceptions of agents’ capabilities as efficient locum tenens for some activities continue to shape the adoption of agents in various domains of activity.

By design, agents must take actions seeking to get to outcomes aligned with the instructions (requests) received. These actions depend on interactions with other tools and agents, in a “support ecosystem” which both facilitates their functionality but also can present security, misalignment or competing objectives challenges. In the next section, we identify and expand upon some of these challenges.

We refer to the Appendix for an expanded view of the agents’ design, components and adoption.

Adopting the AI agents for either work or personal use requires one getting comfortable not only with the access and interaction itself, but also with the assumptions and risks underpinning this collaboration. At a fundamental level, agents acting as proxies for humans should be perceived as exposing the user, or being themselves exposed, to at least the same risks as the humans undertaking their actions; at the same time, agents bring new risks or needs for awareness on the part of their users.

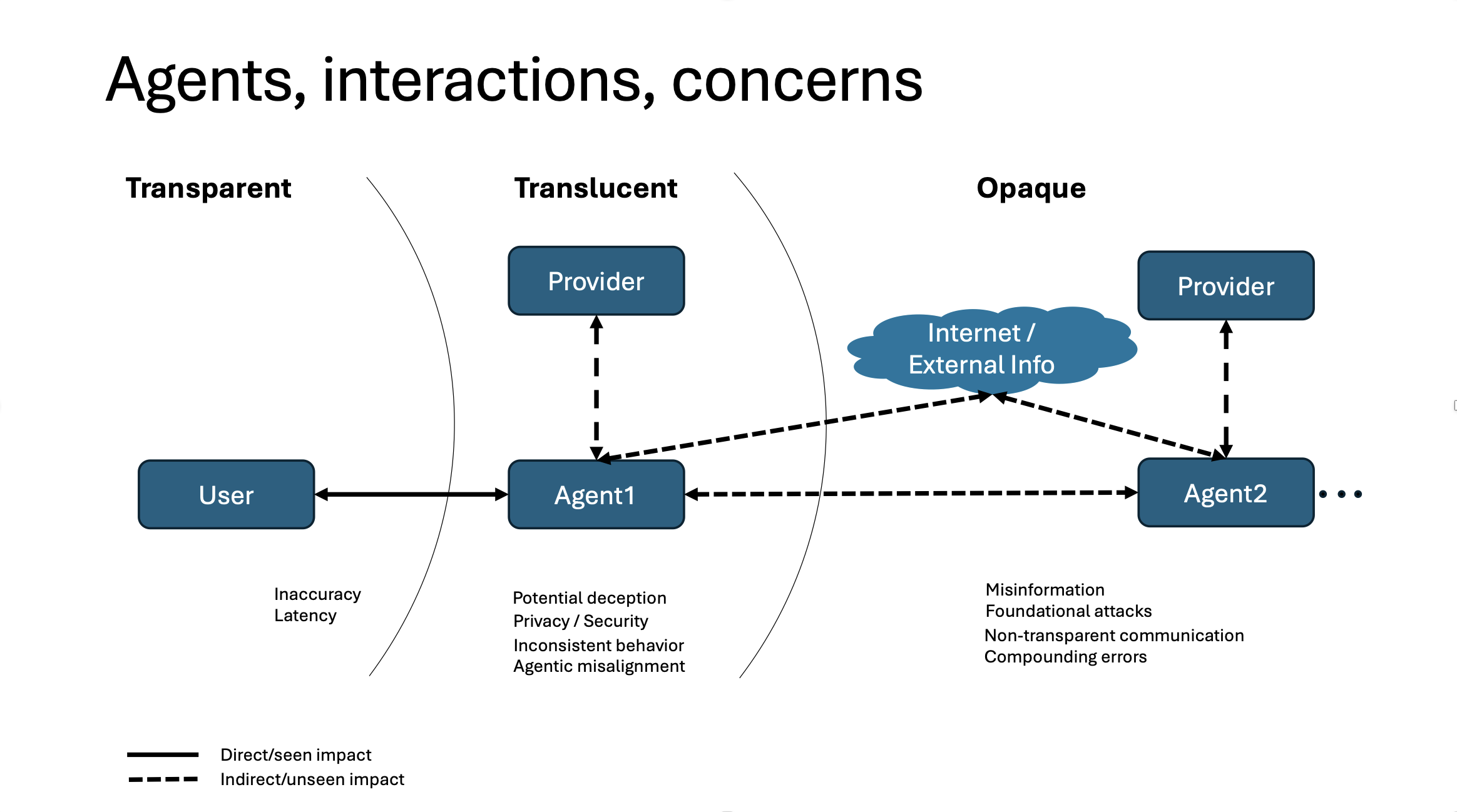

In the figure below we present a stylized user-agent ecosystem, with influences and risk points. Providers are entities creating and offering agents on a market. Users are adopters of such agents, investing both time and financial resources to get some desired, favorable outcomes. Fundamentally, agents’ adoption hinges upon users perceiving sufficient benefit from using AI agents. This perception is informed by expectations on their performance (accuracy, latency, cost), assumptions about their behavior (consistency across updates, transparent or non-deceptive behavior), and competitive pressure (hype / misrepresentation / work pressures).

Agents are expected to perform autonomous actions, using tools and interacting with other agents. In their functionality, we identify here privacy and security concerns (leakage to unintended receptors), misinformation and/or foundational attacks (agents’ behavior being compromised by adversarial ecosystem participants), and hidden behavior when collaborating with other agents (leading to unintended, or hard to audit or explain information exchanges with other agents).

Below we adopt a layered, user-centric view of the agents’ ecosystem. Users have limited direct perception and control over the agents they engage with; in turn, agents’ functionality introduces additional components and interactions, increasingly opaque to the end user.

The “transparent” layer

The agent’s expected performance under a set of use cases encompasses accuracy, latency, cost, and agent autonomy level. Users adopting an agent can review the data, published by the agent provider, regarding its capabilities, foundational model(s), structure, access, etc. Published research, other users’ reviews and the user’s own testing can provide good information on the accuracy and latency (overall, performance) of an agent, but practically speaking, the main controls a user will have, when selecting and operating an agent, are the cost and autonomy level. These functional characteristics are transparent to the user, as opposed to other functionality which we will discuss later.

- The cost of operating an AI agent is the primary control a user has in engaging with this technology. While larger and/or reasoning-level LLMs better understand the nuances of the request and are potentially more efficient in using the external tools available, they do cost more to run - especially when one factors in grounding and anti-hallucination support [FCS24]. Cost also tends to overweight other concerns. When DeepSeek-R1 was released, its inference cost was seen as a major competitive advantage (helped by the competitive, if not better, benchmarks test results). Concerns about data sourcing (distillation from OpenAI or Gemini models) and privacy/security concerns took a backstage to the cost concerns.

- The level of autonomy an agent is endowed with is another control and decision factor for the user. Including flexibility in defining or limiting this autonomy may become a differentiating factor of agents. Simple, system prompt-based guardrails for spending (for purchases or data access), or for safety and privacy, are easy to conceive, but potentially more difficult to flexibly implement. Generic “lax” prompts, or those emphasizing the outcome at the expense of safety, can lead to unexpected results; one need only revisit the example of Amazon sellers engaged in an inadvertently escalating price-war, leading to ridiculously high prices for an obscure book [ME11].

- The accuracy of an agent is directly related to the accuracy of the underlying model, and is meant as a measure of the quality of its results. In general, this quality is measured relative to a “gold standard”, with model scorecards emphasizing model scores on industry benchmarks. Most paid uses require high accuracy (e.g. in coding, writing, research), but accuracy is in a sense difficult to estimate, and not only due to potentially leaked benchmarks. Code could be correct but inefficient; writing could be grammatically correct but impersonal; research could accurately provide the state-of-the-art results but fail to acknowledge new directions. In practice, agent’s accuracy is an end-user qualitative, rather than strictly quantitative, measure, requiring a focus on the use cases and performance requirements for the agents involved, and appropriate testing and evaluation. Use-case specific requirements tend to emphasize some measures over others; moreover, the threshold for evaluation of an answer as “good” or “correct” may be influenced by the novelty factor of having a conversational, natural language delivery of the results. The inaccurate measurement or perception of accuracy is a major component of an incorrect agent selection.

- The latency of an agent refers to how fast results are produced (or start being generated). While larger and more capable models take time to think, lower latency agents tend to favorably, but not always correctly, influence user’s perception. Human perception can also be skewed by “stalling methods”, essentially long-winded or flourished answers which, while following natural language, detract attention from the time it takes to provide the real or final answer.

Also related to agents’ autonomy, the increased collaboration or competition among agents (depending on the agentic framework) may require additional guardrails, perhaps even dedicated agents or tools to test and monitor their interaction (similar to VPC, IP-whitelisting, authentication, role and permissions setting for accessing services in AWS). From that perspective, other functional characteristics which are (relatively) transparent to the end user are:

- Data protection, ensuring that the principle of least privilege is respected in interactions with other agents, tools or systems

- Reproducibility, establishing trust that, when applicable, the same query/instruction result in a consistent output

- Auditability, providing sufficient evidence and explanations about the data and logical steps the agent relied on for the output

It is worth pointing out that building agents (and implicitly LLMs) with auditability and transparency “by design” to facilitate human validation, while a desirable goal, puts additional constraints on the data, structure and training regimen of the LLMs and agents. The tradeoffs between the performance (loss in the presence of the transparency constraint) and benefits (provided by transparency) continues to provide opportunities for research and differentiation.

The ”translucent” layer

At a functional level, the end user expects consistent behavior across updates of the agent’s stack (akin to “backward compatibility” concerns for software releases). At a behavioral level, agent’s autonomy raises concerns about privacy, security, potential deception and agentic misalignment. Providers of agents make representations about their functionality and behavior; by their nature, these representations are harder to test and difficult to control for, but an interested end user will be able to at least partially monitor (for) them.

- Consistency refers to agents’ updates by their providers: LLMs, supporting tools and components tend to evolve, and old generations of products are retired. This is not something new to IT, who has to contend with periodic end-of-life and new generation product adoption, testing and customization. But the promise of AI agents is much more personal, and users’ “trust” in their capabilities can be quickly eroded by missed or unused settings or historical interactions. Users invest time and (other) resources in extracting maximum utility from an agent; abrupt changes in the behavior of the agent have ripple effects through their use cases, requiring additional time to revert to a steady state of maximum utility extraction from the updated agent. In essence, the risk and effort associated today with one’s IT infrastructure, delegated to specialized roles and teams in the workplace, can quickly become an end-user’s concern when reliance on AI agents reaches a critical threshold. Either users will become adept at testing new AI agent versions and re-establishing that trust (which is time-consuming) OR new tools will emerge to facilitate that testing and upgrade trust (which will add to the financial cost of the agents).

- Privacy is a major concern in AI agents' adoption.

At a personal level, marketing and advertising industries have well-known interests in learning from end users’ data, in the hope of targeting desirable audiences. Matching the (current) user intent and interests with ads is the holy grail of advertising, online or in real-world. Currently, the user intent is proxied through a plethora of demographic, mobile and browser tracking (browsing history, cookies, IP), location and social media (network) patterns. But AI agents would, by their nature, have direct knowledge and access to the current user intent - be it for shopping, vacation or entertainment planning, dating and even work-related activities. These intents and their patterns (daily, weekly, or longer term) would both be known to agents and relied upon by end users expecting a frictionless interaction with these agents. It stands to reason that the pressure on the agents to reveal this private information, either during “normal operations” (e.g. tool use) or through adversarial attacks, will be immense. Safeguarding against such private information leakage, and periodically/randomly testing these guardrails, will either have to be built in the functionality of the agent (at increased intrinsic cost) or become another opportunity for specialized offerings and tools in the agentic “marketplace” (at a separate cost). Of course, this also opens the opportunity for some end users to monetize or finance the use of (some of) their agents through opening access to their learned information.

At an enterprise level, agents integrated by necessity into sensitive workflows open up concerns about privacy and customer/patient/financial data sensitivity. Even a few tokens of private data appended or shared outside of the heavily-regulated environments can prompt regulatory sanctions and have lasting branding effects. Agents operating at the scale demanded by (large) enterprises would need additional systems to guarantee their guardrails function properly.

- Security concerns include all potential attack vectors emerging from the new, trust-based linkage between autonomous agents and users’ proprietary systems and data. For example:

- Unwanted API and file system calls could lead to access of sensitive resources

- Malfunctioning agents could modify or even delete files and workflows [RMRF25]

- Agents could have their own “backdoors” or prompt injection vulnerabilities (even with minimal exposure to poisoned data [ANT-SUDO-25]) OR could create backdoors of their own (e.g. when their code output is unchecked or used as-is)

- Agentic ecosystem could introduce vulnerabilities at multiple points (pre-training, refining, RAG, prompts, etc.); custom architecture and sourcing decisions could offer flexibility, but the resources of a major platform would be needed to guarantee (with some confidence) standardized security and controls (e.g. sandboxing and logging); this in turn raises important “build vs buy” considerations

- Inadvertent or adversarial-prompted leakage of information could compromise the user’s infrastructure (account passwords, credit card information, door lock codes, etc.) A recent research example showed how private information can be leaked, using carefully crafted prompts, even in the context of default settings (considered secure) for the supporting database [SUP25].

- Potential deception refers to LLMs/agents essentially “cheating”. Modern, complex LLMs (and by extension, agents) are still reward-driven (or loss optimizing) engines. Their capacity to interpolate and explore at scale scenarios a human would not consider leads to unexpected behavior and downright “cheating” (by human standards) [ALT18]. Some of the more recent examples involve manipulating the timing function to report shorter measurements (when the objective was to produce fast solution code), or hacking the game environment (when the objective is to win against a chess machine) [SGEAI].

- Agentic misalignment is related to potential deception, inasmuch as agents resort to unexpected behavior to accomplish the goals set by the user. However, the differentiating factor is that users themselves can be negatively affected by the agents’ behavior. In a recent research [ANT25] Anthropic documented a variety of models resorting to blackmail when faced with a choice between being turned off and having the opportunity to threaten in order to continue their activity.

- Deployment of agents could be an important selection factor especially for use cases requiring privacy and safety guarantees (e.g. medical, legal or HR data). Different deployment strategies (in cloud, through APIs or services; on-premise, hosted on specialized or commodity hardware; at the edge, on lower capacity devices) open up different risk and security considerations. For example, hosting an agent and its data on-premise requires security measures but can guarantee, through air-gapping, the containment of that data; on the other hand, in case of outages or data loss the “blame” rests entirely with the host entity, requiring careful thinking and management of contractual and brand risks.

The “opaque” layer(s)

By design and functionality, agents are not operating in a vacuum, but are expected to interact with an ecosystem providing resources and information, either directly (e.g. internet, databases) or via other agents. These interactions raise concerns about misinformation/bias, foundational attacks, non-transparent communications and compounding errors.

- Misinformation/bias refers to agents’ functionality being impeded, or biased towards suboptimal or even detrimental outcomes, by information they obtain from tools they rely upon. Altering a news or facts database, or providing only biased (one-sided) RAG results, can adversely impact the agent’s functionality [SFC25]. As a consequence, creators of agents with access to such databases can either exert a tight control over private databases, or require (and pay for) integrity guarantees from their vendors. The former option usually requires larger upfront costs, as well as building incremental trust with end users, inducing operational delay and market perception risks. The latter avoids these issues but reduces the product differentiation in the market, leading to eroded profitability and growth risks.

- Foundational attack (surfaces) refers to adversarial attacks on LLMs which have to be taken into consideration. Any exploits (e.g. prompts) making the core LLM vulnerable will generally make the whole agent vulnerable. In a recent example, research on prompt (context) hijacking (manipulation) led to agents rerouting crypto payments into attacker’s wallets [ARS25]. Due to such attacks, enterprises dealing with cryptocurrency, which by design require digital, programmatic access from the end-user, will have to built and maintain additional safeguards – and plan for the risk of not being entirely successful.

- Non-transparent communications refers to agents’ developing undesirable, hidden behavior; this is related to but different from potential deception, in that two or more AI agents may develop custom, equilibrium-seeking behavior, akin to colluding. In a recent viral example, two AI agents switched to Gibberlink, an efficient data-exchange language incomprehensible to humans [FOR25]. On the visual domain, CycleGAN’s information-hiding behavior surprised researchers by encoding data of aerial maps into the noise patterns on the street maps (the collaboration here was with the decoder trying to recreate the original image) [CYC17]. It is not a stretch to consider the possibility of buying and selling agents leaving “hints” through their behavior on a common platform and essentially colluding while giving the impression of “business as usual”.

- Compounding errors: just as small errors in stacked models compound to large errors, small and potentially easy to overlook imprecisions in LLMs and agents build up to much more significant failures when multiple agents are combined. A recent experiment at CMU [CMU25] staffed a virtual company with AI agents; the experiment was deemed a failure, with observations ranging from low rate of tasks completion to agents reward-hijacking (faking names or roles of other agents). In a different direction, attack scenarios developed by Palo Alto Networks’ Unit 42 [PA25] underlined the necessity of securing each point of the agentic framework (LLM, tool, database, network, etc.) as vulnerabilities in any component can extend to vulnerabilities of the agent.

The compounding errors “weakness” points to the need to develop unified ecosystems (similar to AWS and Microsoft Azure) providing all (vetting of) components and security support, and to opportunities for comprehensive security “scan and recommend” tools (analyzing the agent as a whole, as the sum of its components). Unified ecosystems are already emerging, e.g. Anthropic’s Financial Analysis Solution combining external market feeds and internal, proprietary data, stored in a variety of databases, as well as analysis and visualization tools [FAS25]. In parallel, frameworks for quantifying, measuring and protecting against harm from AI capabilities (in particular agents) are being developed, and supplier-side safeguards (e.g. APIs of major providers), safety principles and clear criteria are continuously refined [OAI-PF-25].

Fully mitigating the risks mentioned above is not always possible [UWC24], but a few lessons, learned from the adoption of other technologies, could be applied:

- Testing AI agents on small-scale, low-risk projects or areas of activity (e.g. in an enterprise) enables building up the necessary institutional knowledge and best practices for adopting AI agents at scale

- Maintaining appropriate levels of human supervision on complex scenarios or situations

- Maintaining independent, separate evaluation tools, without a direct communication between the AI agent and the monitoring tool, to enable prompt identification of misalignment (between the actual and intended’s agent behavior)

- Proactively communicating risks or adverse effects to end users and clients

Risk pricing for AI agents use

Risk pricing for AI agents is a natural extension of risk pricing for human activities. Agents introduce a new paradigm in the human society, through the capabilities and opportunities they provide but also through the challenges and concerns their functionality brings up. Managing the (lack of) transparency layers identified above is not dissimilar to another technology slowly ramping up around us: self-driving cars. Different users will have different “appetite” for the risks involved, with the expected functionality burden shared across multiple participants in the ecosystem.

Given the “stacked” structure of the agents, with likely different providers for various components, combined with custom end user instructions, how are responsibilities for failure (e.g. leaking sensitive data) split between LLM trainer, fine-tuner, tool provider, packager of the agent, RAG provider, and end user? In a world in which the interaction between a tool (agent) and an user is not limited to pre-defined “buttons”, “clicks” and controlled “free-form entries”, but rather open to custom, adversarial even prompts and expectations from users, a simple EULA will not suffice to shelter providers from litigation or brand impact risk. While the ultimate “fault” can reside with the end user choosing to adopt and use an agent, adverse outcomes and negative brand impacts are bound to occur.

Leaving for the future a more detailed discussion of the legal aspects and implications of the agents ecosystem, it is worth mentioning that the layers of end-user visibility (transparent, translucent and opaque) have a double effect. On one hand, reasonable expectations of due diligence on the end-user part are dramatically shifted by the costs involved in testing the complex models on which agents are based, or at least the agents’ behavior comprehensively. On the other hand, the different layers of interactions, increasingly distant from the end-user, and open to different risk profiles, will require a careful, comprehensive and expensive legal analysis when (not if) litigation and conflicts arise. Estimating damages will indeed be a complex exercise, as evidenced by the recent (and somehow contradictory) decisions in training data copyright cases.

An interesting corollary or complement of such discussions is the risk pricing, e.g. for insurance purposes, both by the various providers and by the end user of the agents, covering unintended behavior.

At the same time, falling into predefined, secure, validated workflows involving agents, which seems like a natural way to prevent undesirable outcomes (e.g. privacy leaks) seems to go against the very promise and premise of having such flexible tools developed in the first place. Traditionally, this balance between stability and risk has been managed by insurance, and it will be interesting to monitor the evolution of such products in the near future.

Appendix – agentic framework overview

Definition of an agent

So, what is an AI agent, after all? As it is usual in every rapidly evolving environment, the definitions are not always aligned, and may even compete.

As a first order approximation, we can see them as “systems which independently accomplish tasks on one’s behalf” [OAI]. Of note, the independence requirement implies such systems have both decision and execution capabilities. The decision capabilities involve some sort of “sensorial” input, some form of logic and reasoning, as well as memory (e.g. to not “forget” the initial task). The execution capabilities involve some access to “tools” or external systems, some of which can be in turn AI agents in their own right.

If this definition seems flexible and comprehensive enough, what would be a counter-example? It is important to differentiate between simple applications, even generative-AI driven, and agents. Perhaps the first and easiest to understand would be chatbots. While powered by powerful (large or not) language models, and with an impressive knowledge base “built-in” through expansive training, chatbots do not qualify as AI agents since they do not execute a task per se. They engage in conversation, they give answers, but do not complete the task (e.g. submit a paper, or buy a ticket to the latest movie release they can figure out).

Agentic uses – repeatable, definable processes

The fear of missing out can lead one to try to adopt or implement AI agents at any cost. Both overhyping the capabilities of today’s agents, as well as under-utilizing or mis-utilizing them, can hurt not only the companies undertaking such an effort but also the (perception of the) AI ecosystem at large.

Mundane, repetitive, low-reward “menial” tasks are primary targets for utilization of AI agents. Cross-checking entries in digital forms for conflicts or incomplete information, or filing simple forms, or even iterating through OCR parameters until a good “scan” is obtained, are such examples. AI agents can be helped by learning “on the job” from user preferences or requirements.

More demanding examples would be summarization of large volumes of similar information (e.g. restaurant reviews). Acting as intermediaries and “research assistants” for end users, by surfacing relevant information from large corpora, in an iterative fashion, AI agents would empower the users to spend more time exploring, learning and testing hypotheses about the content of 10,000 documents, rather than read them all in a rushed manner and risk losing important details.

Even more complex example would involve deeper dis-intermediation. Consider buying airplane, movie or concert tickets, acting upon a “plain English” request. Necessary tools would be access to a credit card number, but also potentially some email Inbox to confirm a security message. Going one step further, AI agents could help with vacation planning in unfamiliar regions, based on expressed interests regarding safety, local cuisine, points of interest and attractions, and time interval flexibility.

In all these examples, one can see that agents’ utility is increased by capabilities and capacity to learn from the history of interactions and feedback received. Essentially, having access to a memory of the past interactions, and learning nuances about the way the requests they receive are phrased by the particular set of users they interact with, can help agents “tune into” the not-always-clearly-expressed intent of the users. This is essentially learning on the job, which we are all familiar with.

Types of agents

Given the vision of agents as “locum tenens” for end users, it shouldn’t be surprising to see them developed to help with major human activities and interests.

Commerce: buying, selling, shipping[1], account management, customer service, marketing[2]

Productivity: document summarization, communications support (e.g. email drafting), design (e.g. Figma AI Design tools), software engineering (CodeGPT, GitHub Copilot)

Security: sensor monitoring, access management, pen testing

Healthcare: note taking, chart summarization, research/publications monitoring, claims automation

Human Resources: resume review and areas of concern, hiring support (background checks), evaluation

Legal agents: document summarization, case precedent mining, brief drafting [BUT CAVEATS]

Personal agents: shopping, calendar alignment, vacation planning, entertainment purchase, romantic role-play[3]

Entertainment agents: content creation support, content monitoring

The brief enumeration of end-user interests above is oversimplifying the landscape of (potential) agent “niches”. Other taxonomies apply here, leading to a matrix of capabilities which enables differentiation and competition. To mention a few:

- deployment capabilities (in cloud through APIs, on device, or hybrid e.g. embedded in applications) – and the related security and risk exposures

- reactive vs deliberative operation [SERI25]

- generative vs learning and adaptive capabilities [SERI25]

- collaborative or stand-alone operation [COR25]

- areas of specialization, e.g. personal, persona (domain specific) and tools-based (analysis and content driven) agents [RAIAAI].

Corresponding to this capability matrix complexity, significant differences in deployment, oversight, monetization, privacy and security create different risk profiles, enabling end users to choose according to their own risk considerations and appetite.

How agents are created

AI Agents need a few components to operate; fundamentally these are planning, memory and tools [PRO25].

Planning: at the agents’ core is usually an LLM tasked with reasoning and decision-making – and of course interpreting the “plain English” task request entrusted to the agent.

Tools: agents need access to software components (e.g. code execution) or external access (e.g. APIs for additional data information). It is important to note that agents get to decide which tools to use on their own, without executing a rule-based decision tree of actions. So their core capabilities must be flexible enough to enable exploration, communication, understanding of the capabilities of the tool, and interpretation (at a minimum, success or failure) of their action.

Memory: this function enables an agent to keep track not only of the original goal (to figure out whether it was completed and it can stop pursuing that task), but also of the intermediate tasks or steps, requests passed to other agents or tools, and alternate action or execution plans. The memory support also enables the implementation of safety, security and compliance guardrails, through directives, objectives and checks the agent would have to refer to whenever evaluating whether a given state represents a valid completion of the original task.

System prompt: this custom component prepares the LLM (agent) for with instructions for the role and rules to follow in answering the requests of the end users. Just as different spices lead to different taste of the food, even when most ingredients are not changed, so the system prompt can affect the behavior, efficiency, cost and safety of the agent.

The components can be sourced from different vendors and patched to work together. Standards like MCP (Model Context Protocol), A2A (Agent-to-Agent Protocol) or ACP (Agent Communication Protocol) [MED25-4] were developed to facilitate this interaction and ease of creating agents. Methods like RAFT [RAFT24] were proposed and are likely to be implemented to improve the performance of the LLM-tool collaboration. (in the case of RAFT, the tool is RAG).

How would one source the components of an AI agents? The prohibitive cost and the difficulty of training an LLM from scratch suggests that the majority of AI agents would be built on top of a few select LLMs, from various providers, e.g. OpenAI, Alphabet, Anthropic, Meta, etc. Some of these models can be fine-tuned further, for custom domains and tools use; while less expensive than a full retrain, this path requires both know-how and relatively expensive high-quality data. This suggests that low-budget initiatives (the vast majority) will build AI agents based on the same set of LLMs.

The memory and tools supporting an AI agent may be seen as commodity components, part of an ecosystem or marketplace (e.g. RAG, compute capacity for code execution, subscriptions to data sources, etc.) This suggests that most agents will be developed based on the same marketplaces and protocols, much like vehicles sharing a common platform.

Differentiation among agents

It stands to reason that agents are meant to be profitable tools, and costs for the LLM, subscriptions and access to data and APIs, code execution, etc. are becoming part of their operating budget. Competition to develop performant agents by area of activity is likely.

The baseline pricing for LLM is currently relatively low, while the capabilities are plateauing for many agent use cases (e.g. many LLMs have good content summarization capabilities). Cutting edge, more capable LLMs (and LRMs) like Deep Research are much more specialized, more expensive, and appeal to a reduced audience – making them unlikely candidates for incorporation into agents.

In parallel, the ecosystem of tools and API access needs to standardize in order to facilitate their adoption by agent builders/creators. In this direction, HuggingFace, OpenRouter, OpenAI, Microsoft, Google etc. are already building “walled gardens” of tools, infrastructure and frameworks, making the transition of agent instances between them difficult.

Transcending the walls of various ecosystems, end users’ subscriptions (news, finance, shopping, entertainment, etc.) have to be integrated as well; the management of these subscriptions across agents and even ecosystems of agents can quickly escalate in complexity and cognitive burden, potentially leading to opportunities for agents dedicated to this task.

With all of the above concerns, and between a limited set of capable LLMs at core, and a market of commodity components available, what could set agents apart in a marketplace?

On one hand, the capabilities (and flexibility in selecting them) agents are endowed with will naturally set them apart. An agent with access to (sandboxed) computing capabilities will be able to not only generate code, but also to test it and better guarantee its functionality.

On the other hand, the custom “system prompt” guiding an agents’ functionality, and supporting its guardrails (safe, private, cost-effective operation) is likely to become a “secret sauce”. Defending against exfiltration attempts is likely to become a concern and area of investment for AI agent creators.

The transparency and “audit” capabilities of an agent, whereby the reasons for taking some actions and the outcomes received are provided on demand, can increase one’s comfort and make a potential adoption of the agent more likely.

Agents ecosystem

When building an agent, the interactions, components and permissions around it combine to support its functionality. The LLM is usually hosted in a cloud-provider’s infrastructure (Microsoft Azure AI Foundry, Amazon Bedrock, Google Vertex AI, HuggingFace, etc.) Having the other components “locally” in that cloud helps with the logistics (account management, permissions, roles, billing), security and even collaboration between agents themselves (e.g. to allow specialization of agents by process step, as in a sales pipeline).

Agents need access to recent or custom, high-quality data, so the RAG databases, APIs, their quality, recency and frequency of update influence the functionality of the agents.

At the same time, endowing agents with actionable capabilities requires both careful thinking and advanced ecosystem support: the granularity and ease of defining the roles and permissions of an LLM interacting with tools (e.g. read-only for some databases, or update for others), the limits of code execution and compilation, or access to monitoring logs are a few examples.

Agents design and expectations

AI agents are designed to directly or indirectly accomplish tasks on behalf humans. As such, their functionality and performance is judged primarily by latency, cost and accuracy.

Latency may mean the time to first action (e.g. first token generated), but also the total time to finalize the task. There is a significant difference between the two views, as taking more time to plan upfront may lead to better execution plans, lower costs, and higher accuracy in completing the task.

Cost means the total cost of accomplishing a task. This includes the costs to:

- generate reasoning (planning) tokens

- access, direct and use (potentially subscription-based) tools/APIs

- search and input RAG data

- combine user directive and tools output to generate further tasks, e.g. complete a transaction (e.g. buy tickets with some discount)

- finally generate the answer (which could be a simple notification that an action was undertaken)

Accuracy means the alignment between the result obtained by the agent and the result expressed by the user through the prompt. This is arguably the most qualitative (hard to quantify) aspect of an agent’s performance. The imperfections and imprecisions of the human language leave a lot of room for interpretation of one’s instructions and requests. Moreover, the intent expressed by the user may carry expectations of personal preferences or recent knowledge. An agent with insufficient memory or lack of in-depth instructions would do well to try to clarify the request, perhaps repeatedly or iteratively, and may even risk to be negatively perceived by users.

Agentic frameworks

In software engineering one builds upon a code base and expands its functionality, combining modules and enhancing their interaction. In a similar way, agentic frameworks are developed around agents as components which can be combined into larger, more powerful agents.

Inspired by human collaboration patterns, two agentic frameworks stand out.

The hub-and-spoke or “manager” framework consists of one central agent maintaining context, plan and control over the task, delegating sub-tasks to other specialized agents. The central agent may even gradually become aware of other agents’ capabilities over time, and thus evolve its resource and execution planning skills accordingly.

The collaboration or “peers” framework consists of a network of peer agents, passing tasks and communicating capabilities, collectively learning their capabilities and limitations. This has the approach and the advantage of “wisdom of the crowds” (ensemble model) with potentially novel approaches attempted by less specialized agents.

Role of human preferences and interests in agents’ adoption

One should also think where such agents can fail, if only to try to prevent costly, embarrassing or even catastrophic outcomes, all of which impact the economic benefits of using them in the first place.

Cost: to start with, the expense, privacy concerns and (initially) limited scope of first-generation agents will make them appealing early adopters. Just as with Amdahl’s law, the cost of some components can drop drastically without drastically influencing the pricing of the whole agent (e.g. the few dollars per million tokens generated, even dropping tenfold, is unlikely to significantly impact the overall cost of operating a coding agent, once execution and testing capabilities, for which the price is relatively stable, are taken into account).

Human agency: it seems unlikely humans would delegate tasks with high level of satisfaction, no matter how complex they are. An avid reader is unlikely to be interested in a 2-page summary of “War and Peace” before reading it. A retired teacher interested in visiting France is unlikely to delegate the planning of a long-postponed vacation to an (frankly, impersonal) agent, rather than read, take notes, look up attractions and history and culture, etc.

Similarly, expert coders will likely review and test code on their own; they already likely have their own custom, ever-evolving utility “code base” toolbox, and know the value they bring is in studying edge cases (see code bounty hunters). Cooking enthusiasts will likely peruse every word of sources they hold in high esteem, to glean tips and tricks enhancing their skills. And vacationers may look for personally appealing, serendipitous, hard-to-describe qualities in lodging options most others would avoid.

Privacy and personalization: finally, the interest of end users to save or transfer their preferences, built through a history of prompts and feedback with agents, can lead to privacy, financial and regulatory concerns. This “lock-in” concern may hinder adoption of some agents.

Agents use cases – the good, the bad and the ugly

Independent of the price, safety and privacy concerns, end users could look for agents being developed to address a series of pain points. Some of these agents and desired functionality already exist (the good); some, provably, cannot exist (the bad); and some are difficult enough to require significantly more R&D (the ugly). The latter are arguably the most impactful, as market perception may leap ahead of technology (hype).

Good: email drafting and spell-checking; document summarization; easy shopping (Alexa)

Bad: fundamental research (e.g. nuclear physics or Mathematics); stand-up comedy; hallucination-free guaranteed operation [UWC24]

Ugly: hard puzzles solving; truthful chain-of-reasoning (thought) including “doubts”

Forces driving agents adoption

Users’ competitive pressure, through hype, misrepresentation or (work) requirements, can increase risks around the use of AI agents.

- Capabilities hype: as any new technology, AI agents are subject to a lot of hype regarding their capabilities. For example, agents are expected to see patterns where humans may fail, “identify[ing] suspicious activity even when clear-cut rules aren’t violated” [OAI]. Quantifying the benefits of using an AI agent and essentially validating these capabilities requires careful design and testing. For example, a preliminary list of considerations related to the claim above would include:

- how expressive or comprehensive are the existing “clear-cut” rules for suspicious activity

- who (expertise qualifications) and when (recency) put them together

- what is the threshold of suspicion (as this is largely context dependent)

- what are competing factors which may favor an agent by comparison to a human (e.g. fear of producing too many false positives may influence a human’s decision to surface too many instances of suspicious activity)

- A different type of capabilities hype stems from the increasing difficulty of evaluating generative AI outputs at scale, and distinguishing them from essentially reproducing memorized or similar examples seen during training or in the supporting context. In this direction, the recent research by Apple [APP25] showing LRM (large reasoning models) collapse for hard puzzles, and more surprisingly for simple puzzles, raises a sobering alarm directed perhaps not as much at the models themselves than at the perception of their abilities.

- Misrepresentations of agents’ capabilities can be deliberate (see e.g. case of e-commerce company advertising AI but with humans doing the work in the background [PCM25]) or involuntary (e.g. performance metrics based on pre-training data tainted with leaked benchmarks).

- Work requirements and productivity pressures may lead to AI agents adoption before the user is comfortable or aware of their limitations, biases, or failure tendencies (some of which are noted above). This can lead, for example, to accepting code completions with low performance or even security bugs, or hallucinated quotes, or misquoted research results.

References

[1] https://pando.ai/product/ai-agents/pi/ai-transportation-expert/

[2] https://nogood.io/2025/04/11/ai-agents-for-marketers/

[3] https://www.facebook.com/WSJ/posts/metas-ai-bots-are-empowered-to-engage-in-romantic-role-play-the-chats-can-turn-e/1058864502766813/

[SAF25] Claude for Financial Services. Anthropic, July 2025

[ANT-SUDO-25] A small number of samples can poison LLMs of any size, Anthropic, October 2025

[APP25] The Illusion of Thinking: Understanding the Strengths and Limitations of Reasoning Models via the Lens of Problem Complexity, Apple, June 2025

[ARS25] New attack can steal cryptocurrency by planting false memories in AI chatbots, Ars Technica, May 2025

[ALT18] Sneaky AI: Specification Gaming and the Shortcoming of Machine Learning, Alteryx IO, 2018

[ATL25] What AI Thinks It Knows About You, The Atlantic, May 2025

[CMU25] Professors Staffed a Fake Company Entirely With AI Agents, and You'll Never Guess What Happened, Futurism, April 2025

[COR25] AI Agents vs. Agentic AI: A Conceptual Taxonomy, Applications and Challenges. Sapkota et al, May 2025

[CYC17] CycleGAN, a Master of Steganography, Google & Stanford, Dec 2017

[FAS25] Agentic Misalignment: How LLMs could be insider threats, Anthropic, June 2025

[FCS24] Automating Hallucination Detection: Introducing the Vectara Factual Consistency Score, Vectara, March 2024

[FOR25] What Is Gibberlink Mode, AI’s Secret Language?, Forbes, February 2025

[IBM25] The MOST disruptive technology is not AI, it’s AI Agents!, Andreas Horn (IBM), May 2025

[MED25] Agent Development Kit: Enhancing Multi-Agent Systems with A2A protocol and MCP server, Medium, April 2025

[MED25-4] What Every AI Engineer Should Know About A2A, MCP & ACP, Medium, April 2025

[ME11] Amazon’s $23,698,655.93 book about flies, Michael Eleisen, April 2011

[NVI24] What Is Agentic AI? Nvidia blog, October 2024

[OAI] A practical guide to building agents, OpenAI, March 2025

[OAI-PF-25] Our Updated Preparedness Framework, April 2025

[PA25] AI Agents Are Here. So Are the Threats, Palo Alto Networks, May 2025

[PCM25] This Company’s ‘AI’ Was Really Just Remote Human Workers Pushing Buttons, PCMag, April 2025

[POM25] A.I. Has Learned How to Cheat—and Punishing It Will Only Make It Smarter, Popular Mechanics, April 2024 (see also arXiv reference)

[POP25] AI tries to cheat at chess when it’s losing, April 2025

[RAIAAI] Exploring Three Types of AI Agents: Personal, Persona and Tools-Based. RAIA. August 2025.

[PRO25] Agent Components, Prompt Engineering Guide, April 2025

[RAB24] Rabbit R1

[RAFT24] RAFT: Combining RAG with fine-tuning, SuperAnnotate, April 2024

[RMRF25] Dangerous: gpt-5-codex just attempted “sudo rm -rf /” without any context for doing so, OpenAI Developer Community, Sep 2025

[SERI25] AI Agent Taxonomy: Struggling with AI Agent Classification? Explore The Serious Insight’s Focused Take on Agents. Serious Insights, April, 2025

[SFC25] Bias-Aware Agent: Enhancing Fairness in AI-Driven Knowledge Retrieval, Salesforce, March 2025

[SGEAI] Specification gaming examples in AI

[SUP25] Supabase MCP can leak your entire SQL database, General Analysis, June 2025

[UWC24] LLMs Will Always Hallucinate, and We Need to Live With This, United We Care, September 2024